Elena Luzzatto Valentini, the first Italian woman architect (left) and Florence Fulton Hobson, the first Irish woman architect (right), photo: Monica Prencipe research archive (c), Tanja Poppelreuter research archive (c)

For a long time the history of architecture has been written by white European men, says Tanja Poppelreutrer, architectural historian I meet at the conference on Women Architects, Engineers and Historians in the 20th century organized by MoMoWo (Modern Movement Women). Her research on the first Irish woman architect Florence Fulton Hobson immediately grabs my attention. Listening to the following lecture of Monica Prencipe, architect and historian on the first woman architect of Italy, Elena Luzzatto Valentini, I realize these two stories have a lot in common. Quickly I decide to interview both of them. So today, we bring you stories of two women pioneers who are surprisingly relevant to architects even today.

interview by: Milota Sidorova

Florence Hobson Fulton – the first woman architect in Ireland. Elena Luzzatto Valentini – the first woman architect in Italy. Can you introduce us to their stories?

Tanja Poppelreuter (TP): Florence Hobson Fulton was born in 1881. She grew up in Belfast where she went to the Art College and later on she was able to find apprenticeships in architectural practices in Belfast and London. In 1905 she moved back to Belfast where she began working for Belfast Corporation. In 1911 she was the third woman who was licensed by the RIBA (Royal Institute for British Architects). She came from a family of Quakers and her mother was an active suffragette. Her brother John Bulmer Hobson was a famous Irish nationalist. She came from a tolerant family with multi-faceted interests.

During the time she worked for Belfast Corporation, she worked on some public buildings such as an abattoir and built three houses in private practice by the late 1920. She retired in 1936, so it is possible she built more houses that I don’t know about – yet.

Did she work for the Corporation while having her own practice?

TP: I am not sure. In the time span of twenty years these three houses are not that much of on oeuvre and I think she could have managed to work at the Belfast Corporation and in private practice at the same time; at least occasionally. I would need to find out whether she worked full time or part time – I don’t know many details about her career at the Belfast Corporation.

Still she seems to be quite a black sheep for the time.

TP: Well, she was certainly different. She retired in 1936 and after her retirement she married a man 12 years younger than her, which at that time must have been very unusual. But I also don’t know why they married; perhaps they knew each other since a long time already. While the details remain obscure, just the plain facts are quite interesting.

Are Irish architects, academics and students aware of her?

TP: No unfortunately not. Sometimes local historians have heard about her and know her name but little more. Occasionally, people whom I ask about her tell me they heard of her, but then we find out I have asked them about her in the past (laughing). I have found her great-nephew who remembers her and who is very helpful and I was able to enthuse one of my students – Ryan McBride – to write a BA Hons dissertation about her.

What about Elena Luzzatto Valentini?

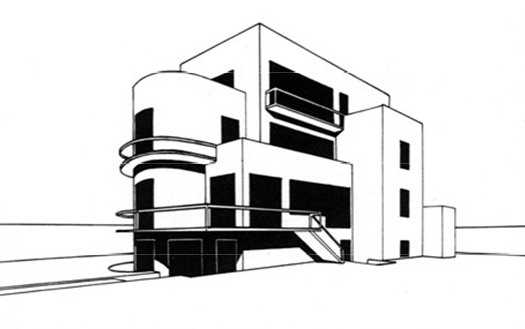

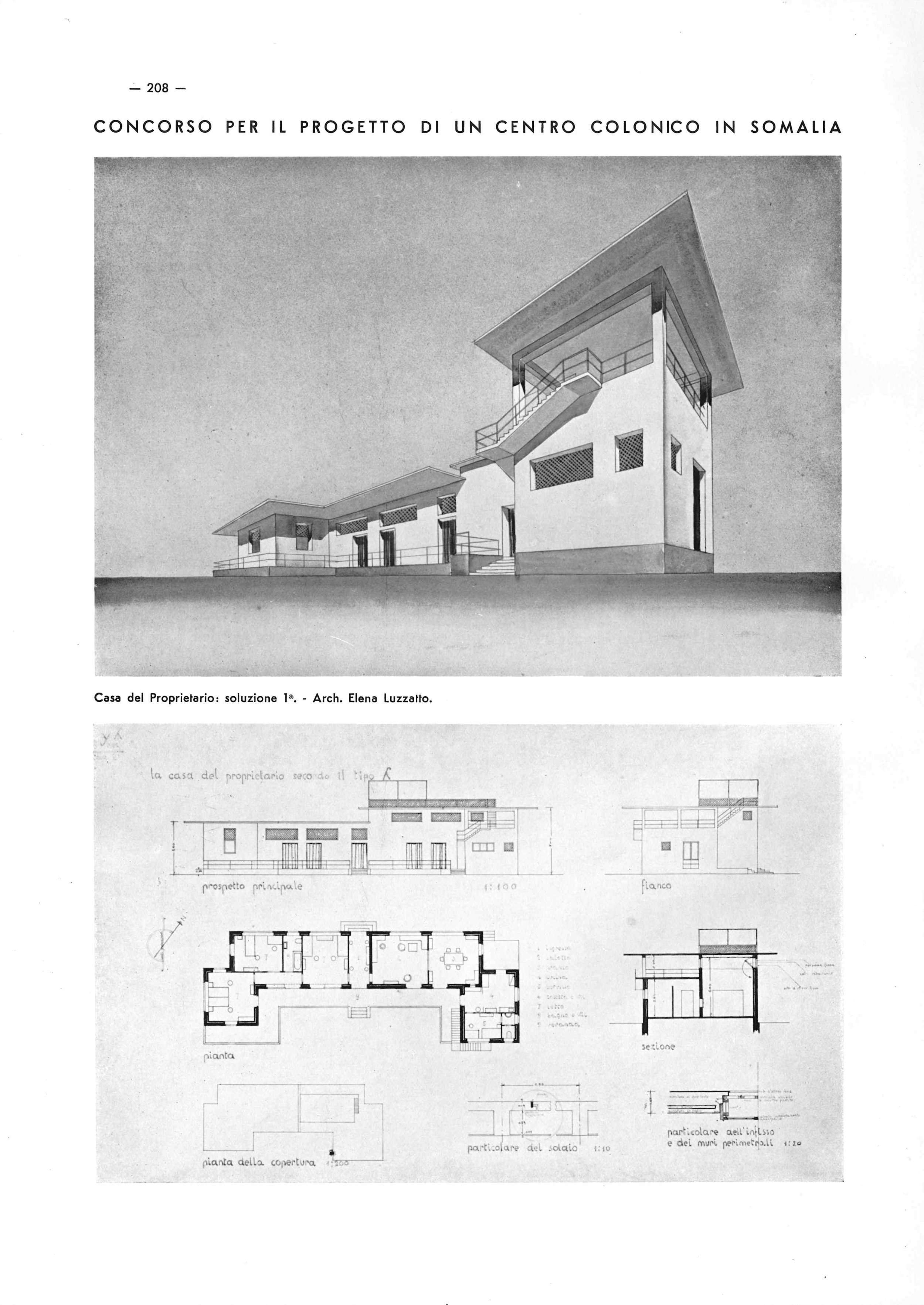

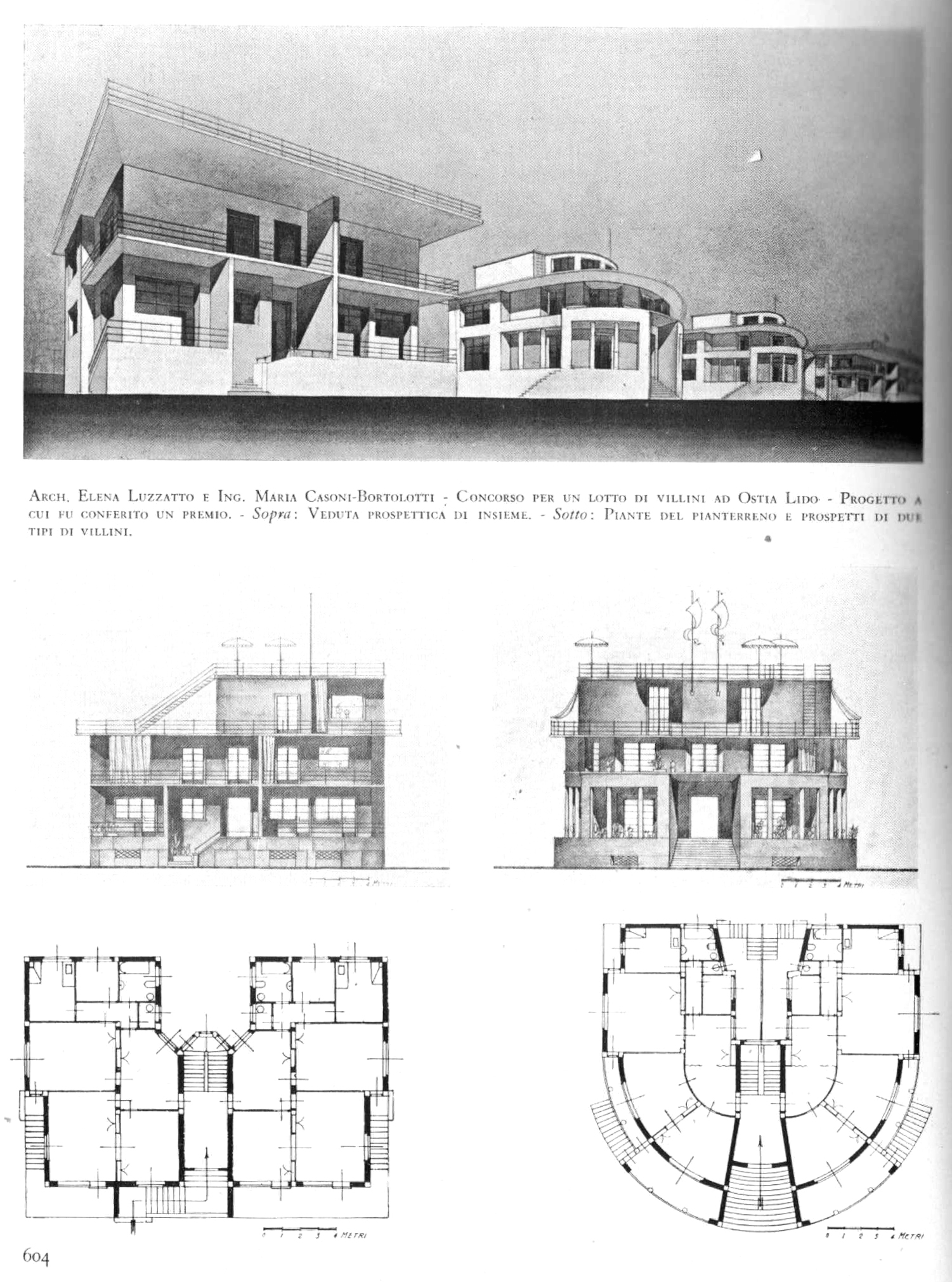

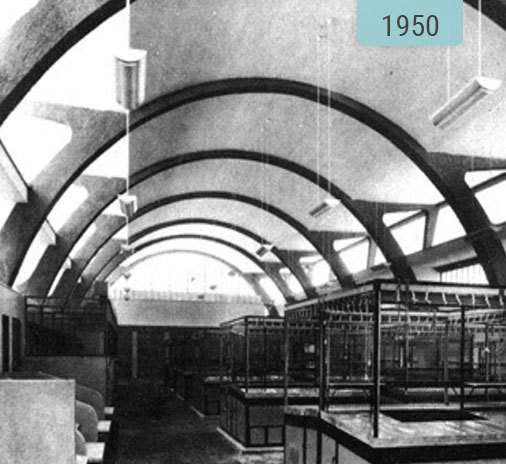

Monica Prencipe (MP): Elena was born a little later - in 1900 - into a quite unusual family setting of Jewish father and a catholic mother. This family background was unusual compared to the typical Italian catholic one. She was the first woman to enroll the school of architecture which opened in 1920 in Rome. After her studies she immediately entered the Governatorato di Roma, which was the town planning office. There, she had the chance to be involved in designing many public buildings like schools, markets or cemeteries. During her career she designed more than 40 buildings and won at least 12 competitions. She worked for the government until 1958 when she retired but kept her own private firm until her final retirement at the age of 77. She became a recognized architect and right after the war in 1950 she was one of few female architects to be exhibited in Italy. She focused on the work and she didn’t write anything, as far as we know. Her collaborations remain widely unknown, and what is known is that she married a catholic engineer at the age of 36; they collaborated on several competitions.

Elena also collaborated not only with men but important women too, for example with the first woman engineer Maria Casoni-Bortolotti or the first Italian woman landscape architect, Maria Teresa Parpagliolo.

When you say, she had the chance to design public buildings, what exactly do you mean by that?

MP: She entered the Governatorato di Roma as a 26 years old woman. In 1934 Mussolini prevented women to work in public institutions. Actually, she was one of only a few who entered public service at the time when women still could. Among women she was the only full architect, not the architectural assistant. Yet, for 20 years she was appointed as a second level architect until 1952. Only in her last 6 years of her public career she was considered to be a first level or ‘full’ architect.

What was her personality?

MP: Considering she didn’t leave any writing or notes, this is a rather difficult question. We are trying to understand her work through her private archive and family memories of her nephew who was very fond of her. What we know is that she was moderate and a hard-working woman. In his memories her nephew mentioned she worked often with a number of psychiatrists. First, she was close to them as a patient, but later on they commissioned her to build their private houses. For me as a researcher this is a very interesting line of investigation. Look, nowadays everyone goes to a psychotherapist, but at that time it must have been a tabu.

So here we have two stories. Can you find some similarities or patterns among them?

TP: In a way their private lives were similar. They both had careers in public service, but neither of them had children. Both married quite late. Elena didn’t married as late as Florence who was almost 60 at the time. Nowadays this is not unheard of, but imagine Rome and Belfast in the 1930’s. They both led quite long lives, Florence died at the age of 97, Elena was 83.

MP: Their family backgrounds are interesting too. In Italy Jewish families usually paid good attention to education of the daughters.

In Belfast, Quakers were also a minority. Her mother was not only an active suffragette but also a hobby archeologist. She seems to have been very social and interested. I think this was the environment in which Florence was taught that it was acceptable to break free from conventions and that becoming the first Irish women architect was perhaps not as frightening as it might have seemed to be.

Tanja Poppelreuter

Elena’s father was a railway engineer and a very educated man. He knew there were more possibilities for women than to be just housewives.

Monica Prencipe

TP: That is true. Also, both belonged to the middle class and their environment expected them to behave in a particular way. From these expectations the obstacles they met with in schools, practices and on building sites emerged. The problem that a women architect might have to climb up a ladder in a skirt, for example, was taken very seriously because it related to modesty and status. For working class women such problems might not have been as pressing – because they had no choice but to work in the factories to survive. For women like Florence working was not so much a matter of survival but more a question of self-realization and self-identification. I can also imagine that, after acquiring the education, working in apprenticeships and the Belfast Corporation, and in private practice she would have been reluctant to give up what she had achieved; which might be why she married late and had no children.

MP: Elena didn’t come from a wealthy family. According to our sources her wealthy relatives, not her father had to pay for her studies. We have found her certificate, at the age of thirty she still lived with her parents in modest conditions.

How are stories of these architects relevant today?

MP: Visibility of interesting stories particularly of women architects is important. Yet, the more I am digging into the research the more I keep asking myself: why she didn’t leave her work to somebody? Has she ever considered herself important? Her nephew often referred to her as a very humble. After finishing big projects like a market or a cemetery, she only said: yes I did it. The PR or star allure was completely absent. Was she aware of how important she was? I don’t think so. She kept working and working. This modest self-conscience is relevant today. Many women work hard and don’t stand out. They deserve their credits, but I think many don’t even understand how valuable their work is.

TP: Who makes history? Who writes it? History is not set in stone; it is changing according to who interprets the facts and which facts are brought forward. For a long time it was white, middle class, European male who was practicing architecture and who was writing about architecture. These groups of people who also knew each other were also situated in central locations such as London, New York, Paris, etc.

I think historians are starting to revisit books on 20th-century architecture in order to ask, for example, where are the women architects? Who worked in collaboration with whom? What does it mean to be innovative and ground-breaking? We are not as ready as we were to believe that one person is able to foster wide-ranging changes alone.

We instead know that there is almost always a support system and we can ask why this support system is not acknowledged. This is just one facet of how history and the contributions of others to the history of architecture can be revisited. Perhaps in 20 years time we have a different view on 20th-century architectural history because research has been conducted that allows for a more inclusive view on the innovations and changes that made 20th-century architecture special. Every little story we find about pioneers, innovators or practitioners will add new perspectives on how our society during the 20th century has developed into what we are today. I think stories need to be reassessed and we have to start telling and teaching history in a more inclusive way. This will perhaps also inform the ways in which we think about the creative process and the people who are working jointly to achieve it.

How we can achieve it?

TP: Just keep on doing what we are doing, publish, write blogs, write articles, books etc. Go to conferences, be curious, avoid stereotypes and preconceptions and try to be as inclusive as we can.

You made a bridge to the next question. Why have you chosen these particular women for your research?

MP: The first answer is, because she was born in my hometown, small town in central Italy. I told myself, wow we have to know more about her. I relate to her because I always had the interest in role of women in the architecture of 20th century. My role model at the university was a woman and she passed me this interest.

TP: Florence Fulton Hobson was actually ‘discovered’ by my Head of School Peter Walker who used her portrait in one of his lectures. I was sitting in the audience thinking Florence … Who?

I was amazed that she was the third woman architect in UK – the first one in Ireland – and that there was a novel about her family but nothing about her work as an architect. I started to wonder about the processes of why and how certain architects – men and women – were selected to be written about and to be remembered. Later on when I set out to write about her I found out about, MoMoWo, Un Dia, Una Arquitecta and other initiatives and realized that these are new ways to channel research to a broad audience.

What is your ambition for your research and how do you see yourself in the future?

MP: As a historian of course I want to go deeper. When you touch topic of women architects in the history, you realize you scratch only the tip of the iceberg. On the other hand I don’t want this to be only about her. I would like to connect all women architects in Rome. I would like to open this new perspective of history of architecture.

When I finish I would like to organize exhibition in my hometown, Rome and spread this knowledge among people. We have these women and we can be proud of them. Besides research I would like to keep doing what I am doing. I would like to stay at the university and also keep working at a small studio. I would like to combine theory and practice as they can go very well together.

TP: I would like to find out about Florence as much as I can and publish my findings in a well-read and established journal. My interest however lies in establishing a wider network of research. This would be on a different topic – exiled German speaking architects who fled Europe in the late 1930s. After finalizing the project on Florence I would like to focus on exiled female architects. The tip of the iceberg Monica mentioned is the right analogy for this project too. At the beginning I knew only about two or three women architect, now, after just a short period of research, I have learned about more than fifteen individuals. So this is a project larger than me. I would therefore like to be able to obtain funding for PhD or post-doc opportunities and perhaps being able to collaborate with several institutions who are interested in refugee and exile studies.

Thank you!

Tanja Poppelreuter (left) and Monica Prencipe (right), photo: Milota Sidorova (c)

Tanja Poppelreuter is a Lecturer in the History and Theory of Architecture at the Belfast School of Architecture, Ulster University. She teaches in the undergraduate as well as postgraduate programmes, supervises PhD theses and conducts research in 20th-century architectural history and theory. She graduated with a PhD in Art History from the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University, Frankfurt/Main, Germany. Her doctoral thesis Das Neue Bauen für den Neuen Menschen (The New Architecture for the New Man published 2007) discusses disparate ideologies prevalent during the 1920s in Germany that sought to reform and renew mankind with the help of architecture. Out of an ubiquitous spirit of optimism at the end of World War One and at the beginning of the Weimar Republic, numerous reform movements developed that expressed the goal to help in developing a renewed culture, society and which were motivated by the belief that an egalitarian age could be spawned which would be ruled by a ‘new man’.

Subsequent to her PhD Tanja was a lecturer in Art History at the Department of Art History at Auckland University, New Zealand before joining the Belfast School of Architecture in 2011. Her main research interests are on the perceptions and development of architectural space in early 20th-century architectural design as well as on German-speaking architects who fled the Nazi regime during the late 1930s.

Monica Prencipe is a trained architect at the University of Bologna, Facolta di Architettura ‘’Aldo Rossi’’. After her master degree, in 2012 Monica Prencipe entered the Scuola di Specializzazione in Beni Architettonici e del Paesaggio at Roma La Sapienza. She is currently a PhD student at the Università Politecnica delle Marche, Ancona (Italy) in History of Modern Architecture, where she focuses her studies on the critic Bruno Zevi and his relationship with Nordic countries. In 2016 she found the private archive held by Mauro Ferroni on Elena Luzzatto Valentini, the first Italian woman architect.