Myriam Ababsa during her visit in Prague, Goethe-Institut Prag, photo (c) Pavel Borecky

Myriam Ababsa is an Algerian-French social geographer and researcher based in Amman, Jordan, where she has collaborated with number of institutions, including French Institute for the Near East, Ifpo or World Bank. She is a former student of the Ecole Normale Supérieure Fontenay-Saint Cloud (1993-1997) and of the Department of Geography (Paris I Panthéon Sorbonne), she holds a PhD in Geography from the University François Rabelais of Tours (2004). In her works, she focuses on the impact of public policies on regional and urban development in Jordan and Syria. She questions governance, public participation in housing policies and service delivery. She authored the Atlas of Jordan. History, Territories, Society , co-edited Cities, Urban Practices and Nation Building in Jordan, Popular Housing and Urban Land Tenure in the Middle East (University of Cairo Press, 2012). Her PhD thesis Raqqa, territoires et pratiques sociales d’une ville syrienne was one of two that received the Syrian Studies Association Best Doctoral Dissertation Prize, in 2006.

Interviewed by Milota Sidorova during her visit of Prague through program Carte Blanche by Goethe-Institut, 25.1.2017, Prague

What is life in the public sphere like in Amman? What role do women play in it?

Men control public space in Amman. This is true for nearly the entire city. Women are expected to follow a set of rules that are never explicitly laid out. First, wear loose cloths and dress with modesty. In Eastern Amman, women must wear the hijab, and over the past ten years a new phenomenon has arisen, whereby women from lower income families have started wearing the niqab. For the most part, it is only Christians, westerners, Asian maids and members of the upper social classes who don’t wear the hijab. Second, avoid being alone at all costs. Walk with a friend, a relative, or even a child. A woman should not be seen out by herself. And finally, avoid going out at night. It isn’t socially acceptable for a woman to walk alone after sunset, except in some commercial areas and in low density, western parts of the city. Disregarding these unwritten rules will often expose women to suggestive remarks and unwanted compliments and/or insults.

Verbal sexual harassment is a major problem for women walking the streets of Amman and seemingly is much more prevalent than in Damascus, Jerusalem or Ramallah. Young men face a lot of frustration, with half of young men living in Jordan unemployed (official statistics indicate that 35 percent of youth today in Jordan are unemployed). They tend to hang out in groups, especially in the evening, and rule the streets of Amman. Syrian women who have come to Jordan seeking refuge (and a third of whom live in Amman), are forced to go out in groups or stay at home for safety. Often foreigners experience high levels of harassment due to prevailing and erroneous stereotypes, with Sri Lankan and Philippine maids facing more severe harassment.

During the day, women are more visible in the streets of Amman as they go about their daily lives: groups of veiled students waiting for public transport to go to school and attending university (50 percent of university students in Jordan are women); young women actively joining the administrations, elderly women and Asian maids doing the groceries. After school the daily ritual continues with family visits taking place after the family meal (usually eaten around 4pm)

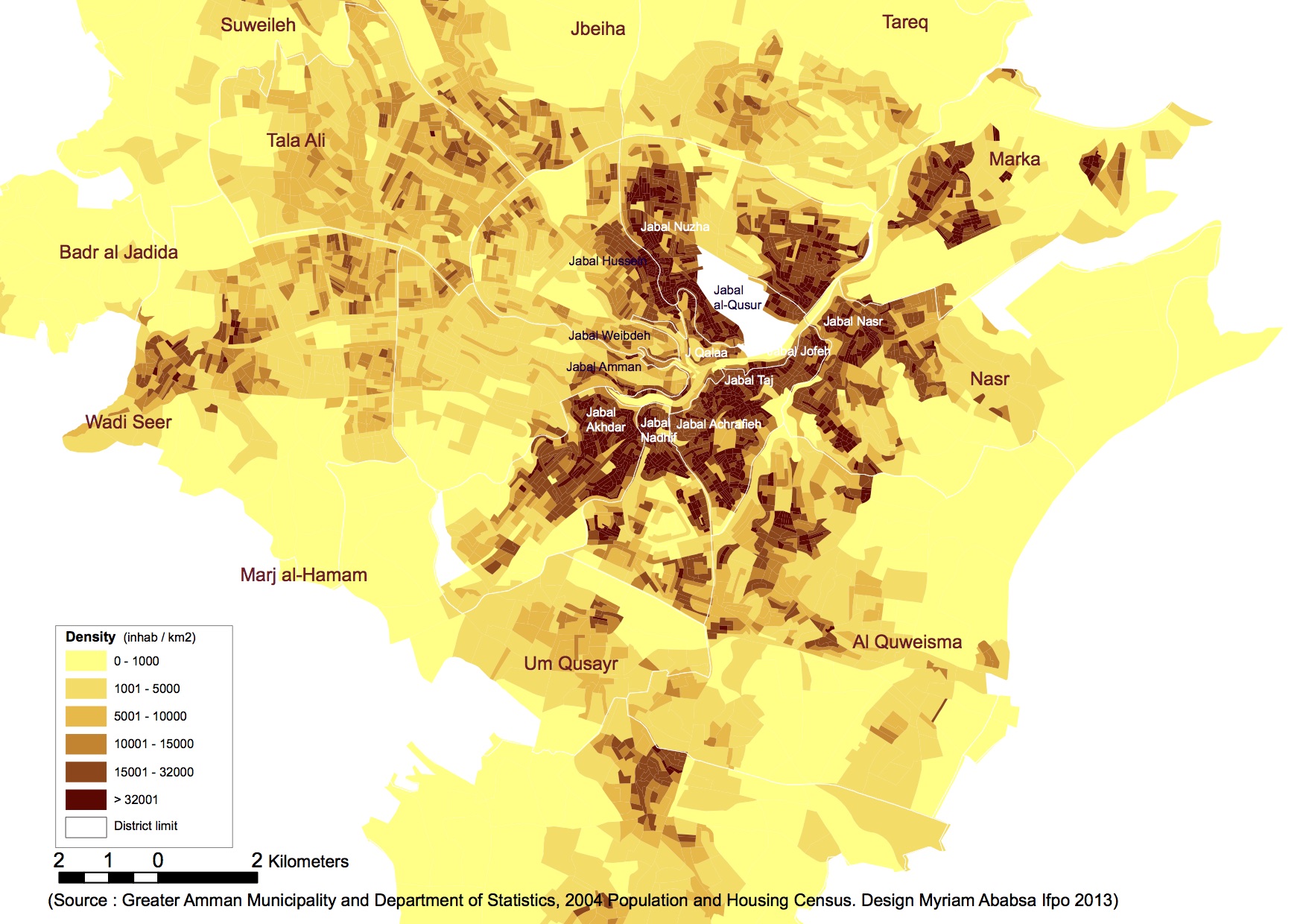

On the whole, women enjoy more freedom in the capital than in Jordan’s smaller and more provincial towns. But again, it all depends on which part of the city you’re in. In reality, it is like Amman is made up of three different cities: East Amman, Central Amman, and West Amman. The largest area of the city, East Amman, is grey, very densely built and heavily populated. It is built informally near the two Palestinian camps of Yarmouk and Jabal Hussein. In these areas you will find many great women who play an active role in the community. However, although many of the women are engaged in social work, there is still a lot of control and oppression felt from their neighbors. In the poorest part of the city, women are deprived of safe public spaces: there are no gardens, no benches, and there is a low level of tolerance.

East Amman, photo (c) Myriam Ababsa

Then you have Central Amman. This area of the city is much more commercial, more mixed, with shops and restaurants. The people in this area tend to be more tolerant. There is a minority Christian population here as well who have a visible presence. It is interesting to note that Christians have been very active in the fight for women’s rights since the 1950s. But then of course Jordan, and in particular Amman, does have a very active community of women rights’ defenders, activists and artists who engage a lot with their cause.

Central Amman, photo (c) Myriam Ababsa

Looking towards Central Amman, photo (c) Myriam Ababsa

The third part of the city is West Amman the most affluent region, which includes Shmeissani, Um Uzeina, Sweifiyeh, Deir Ghbar, Tala Ali, Abdoun, and Dabuq. Policemen guard several private houses here, where members of parliament or ministers live. Here you can enjoy much more freedom. Women can walk alone, go to coffee shops, go to hairdressers etc, they work. They jog very early in the morning (at around 6am). They dress as they wish as they have cars, though a new taxi service for women only has appeared (SheCab).

Boys and girls moving freely on the Rainbow street, West Amman, photo (c) Myriam Ababsa

It could be expected that, as is the case in other Muslim countries, Jordanian women don’t participate in the job market, at least not in an official capacity.

Yes, it is important to remember that Jordan continues to have the lowest level of women’s economic participation in the world. In Jordan, only 13 percent of working professionals are women, comparable to the levels of inequality in Yemen. This is mainly due to the absence of public transportation and to the harassment women face while waiting for the bus or other forms of public transport. Getting to work is a real problem for women. Only 40 percent of the households, the majority of which belong to families from middle and upper classes, own cars.

What kind of jobs are women expected to take in Jordan?

Women mainly work in the public sector, as teachers, as nurses (making up to half of medical professionals). A lot depends on working hours. On the whole, the working day in the public sector begins at 8am and ends at 3pm, in other words during daylight hours. Private companies tend to finish at 5pm, which is after sunset in the winter months. This can be problematic as a lack of public transport and the social constraints on women walking after dark mean that those who don’t own cars are forced to take taxis. This can amount to anything from 60 JD to 90 JD per month. In Jordan the average salary is 350-450 JD (minimum wage is 190JD by law).

Inefficient public transport and the streets dominated by individual cars make free movement of women around Amman rather difficult, photo (c) Pavel Borecky

How do women’s professional lives relate to their private/personal lives?

Some men expect working women to contribute to the household expenses. Culturally it is expected that the man should provide all expenses (eg. rent, school fees, food, clothes, leisure etc.). In theory, women have the right to choose not to support their family. There is also a culture of shame, which means that women and men are prevented from doing certain low skill jobs.

Women’s professional lives are connected to their marriages. Women have to marry young, ideally before 25. Once married, women are expected to take care of their families. 40 percent of weddings in Jordan are among first or second-degree cousins. In many cases, you live just above your mother-in-law, in an apartment built on the second or third floor. The average family has more than three children (3.7 children per woman). Although numbers of children have been declining across the Arab world, in Jordan the rate remains rather high.

When children grow up and leave the home, women are on average, about 40 years old and they want to engage in society. Some of them want to start working; they want to be useful. Some non-governmental organizations (NGO), such as Tatawor, support women to write cover letters and CVs so that they can apply for jobs and get work.

Is there any other implication?

Yes, in Jordan there is a social pressure on women to give up their heritage rights in favor of their brothers. Property ownership is a male domain in Jordan, where women are dependent on men for housing. A patriarchal pattern of power dominates both inheritance and property. While the inheritance rights of women are formally enshrined in the constitution, in Islamic law (Sharia), and in the customary law particularly common in the steppe regions, female heirs continue to face social pressure to renounce their rights in favor of male heirs. Most women either do not receive the share of inheritance that the law entitles them to or they are simply denied their right to housing and land. Besides social pressure, women are deprived of their inheritance in several other ways. One takes the form of a donation to male heirs before a person’s death. Another is when owners and their male heirs choose to leave a property undivided, which prevents female heirs from using or selling their share for years and even decades. In most cases male heirs give symbolic gifts to women, called badal or takrim, which are worth far less than the value of shares they are legally entitled to receive. In general, women are kept in the dark about the real value of assets such as land or an apartment.

A survey conducted in Irbid in 2010 showed that 20 percent of women renounced their shares in their deceased father’s possessions. This is because they face significant pressure from their mothers and/or sisters due to the belief that the father’s possessions should not go to his daughters. The result is that women own only 7 percent of apartments and 7 percent of the land in Jordan which in turn has negative consequences for women who want to enter the world of business. Without an apartment as collateral, women find it difficult to obtain a loan and start a business. Having said that, there have been international movements over the years to change this issue. In 2000, the Global Banking Alliance for Women was created to support female entrepreneurs, including those who do not have assets. In 2012, a Lebanese bank, BLC, launched a women’s empowerment program to provide loans and training for women. Women entrepreneurs are asked to provide sound accounting books for at least three years in order to access loans. This program, however, has not yet been launched in Jordan.

You mentioned there is an active scene of women rights’ defenders, artists supporting women in Jordan. What are their demands? What do they want to achieve for women?

Women’s rights’ defenders have managed to push for better political representation of women in Jordan. Since 2013, 25 percent of municipal council seats must be held by women. In general, Jordanian society is still conservative, with members of Parliament elected through their affiliation to a major tribe and not to a major political party. However, women continue to have poor representation in the National Assembly.

Women, who make up half of the Jordanian population, must go through the mediation of men to exist as citizens. They are unable pass their citizenship on to their children. They need the permission of male family members to obtain passports. This renders women as lesser citizens who are made to present their family status record book for any civil status procedures.

In 1992, Jordan signed the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) but with reservations on three articles: one related to the right for women to pass their citizenship on to their children; another on women’s right to choose their place of residence; and the last one on women’s responsibilities in marriage and its dissolution. In 2009, the Cabinet agreed to withdraw the reservation to Article 15/4 of the Convention thereby granting women the right to choose their residence and to move freely. Prior to this ruling, women would live in their father’s house where they would be recorded in the family book. After marriage, woman was handed over to her husband to be recorded in her husband’s family book. Women continue to face difficulties when they divorce or are widowed. On the whole, only women from the upper class manage to keep the apartment after the death of their husband and it is only really acceptable if they have children.

Amman women walking in the city, always accompanied, photo (c) Pavel Borecky

From what you are saying, woman has to live in the constant presence or guarding of men.

Male guardianship (qawama) of female family members is not only a tradition but is inscribed in the law. According to the Jordanian Personal Status Law (no. 36, 2010) a male blood relative (wa ̄li) has the right to have guardianship of women. If woman is unmarried, under age of 30 or previously married, she must have male guardian. Upon marriage a woman is transferred from her father’s custody to her husband's. In Jordan woman's rights to housing are connected to her status as a wife or a daughter. If the father dies the brothers have the right to sell the house in which the mother and sister(s) are living. Consequently, the fate of a woman depends on the quality of the relationships she haa with male members of their family. In the case of divorce, a woman only has the right to housing if she is nursing or has been granted custody of the children.

Is there a new generation of men and women who live according to western measures and live more equal lives, particularly with regard to family duties?

Of course there are families like this in Jordan. Normally, they have traveled or studied abroad in some of the world’s top universities. They are part of the bourgeoisie. They will invite you over to their homes, they cook in wok, they present modern image. The reality is, however, that for everyday life, the task of cooking is given to Asian maids who live in the home. These women go to galleries, art centers etc. Children of the elite class attend private schools with highly qualified teachers who have come from all over the world, reflecting the image of the global elite and global values. There are many Romanian, Russian, Ukrainian women married to Jordanian men, who studied abroad in the former Soviet Union.

In the traditional family, the woman’s future depends on her husband. It is a terrible thing to say, but it is true. The problem is not so much if you do or do not wear the veil or if you ride the taxi alone, but rather whether your husband allows you to do so.

The quality of a woman’s life depends on the quality of her relationship with her husband.

How is it in your case? You speak about these issues with a certain ease, like they haven’t affected you.

Laughs. I am Algerian-French, and my husband is Palestinian-Swiss. We are integrated, but we know both worlds and we work on both sides. We enjoy freedom as members of the upper middle class, living in a low-density area. But my neighbors do enquire about my guests, especially when my husband travels (!). The moment you are married, and especially to an Arab man, you are fine. No one can judge what your husband allows you to do.

What is it like for women to stay single in Jordan? What if you don’t want to marry, what are your options?

It all depends on your social class. Traditionally, women marry their first or second cousins (ibn al-‘am) as a way of ensuring that women behave correctly, and also as a means of reducing dowry costs. Many middle class Jordanian women who study abroad and return at the age of 27/28 find it very difficult to marry. There is an idea that those who have travelled abroad have grown accustomed to the social freedom of the west. It is really unfair, as most of these students don’t have any romantic relationship whilst studying abroad. I know a lot of brilliant women who studied abroad and did not manage to marry after. Spinsterhood is a real problem for women in Jordan.

It is also difficult for women to remarry once they’re divorced. For men, it isn’t really a problem so long as they can afford it. Often, divorced women remain single until the end of their lives. You can be divorced at 35, 40 and, if you stay in Jordan, you can be certain you’ll have very little love after. It’s awful. So much sadness and frustration!

In the Middle East it’s difficult for men and women to be friends. Of course, it happens, and is tolerated when you are old (over 45, my age (!)). Unfortunately, in our culture everything is sexualized. If you’re a working professional woman and are in a room with a male colleague, the doors must stay open. Even at the cinema, if there are men or women in the room who are not married, the doors stay open.

Here, if people don’t marry or don’t divorce, they have affairs. Is this common in Jordan?

Not very often. It is too dangerous. Jordan and Turkey are countries where you have honour crimes.

How does your work contribute to better conditions of women?

I publish books and papers written in Arabic, English and French. As a social geographer, I’m currently working on social housing policies. In Jordan we’re thinking about how to create a more inclusive society. For example, instead of placing social housing in suburbs, away from the town centre, we are trying to move them to the centre, closer to public gardens, and near to places where you can go with your kids and can go out.

We should also consider the fate of the many divorced women who are often pushed out of their apartments once they have raised their kids. Women are allowed to live with their child in the apartment until he/she is 15 years old. After that they are supposed to go back to their parents. Women’s rights’ activists are currently working with shari’a judges to change this.

Doing advocacy, going to conferences, networking, and engaging in participatory budgets really helps women.

Thank you very much!